The Chadian-Libyan war was waged from 1978 to 1987, but a decisive battle at the end of the conflict earned it the name “The Great Toyota War.”

The name was first coined in a 1984 Time magazine article reporting on Chad’s civil war and was the first mainstream account of the Hilux technical phenomenon. The Chadian-Libyan war wasn’t the first to deploy civilian vehicles in combat but is nevertheless remembered for its innovative and brutally effective asymmetrical tactics. Chad scored a surprise victory by mastering a new kind of mechanized warfare, one that pits cheap, rugged civilian vehicles – the Toyota Hilux often being the vehicle of choice – with tactics designed to exploit the weaknesses of the ponderous tank battalions they were up against.

To understand how a civilian pickup like the Hilux could bring victory to a small attack force with limited technical skills against a fortified enemy boasting modern weapons and overwhelming firepower, consider the geography, infrastructure, and resources of the two sides. Both Chad and Libya are former African colonies. In 1987, the two nations were similar in size: Chad, with a population of five million and area of roughly 495,000 square miles / 1,280,000 square kilometers, and Libya, with 4 million people inhabiting 680,000 square miles / 1,760,000 square kilometers. Libya was rich, Chad was poor. Libya was equipped with a surplus of tanks, aircraft, rockets, and missiles, while Chad lacked the means for a conventional military.

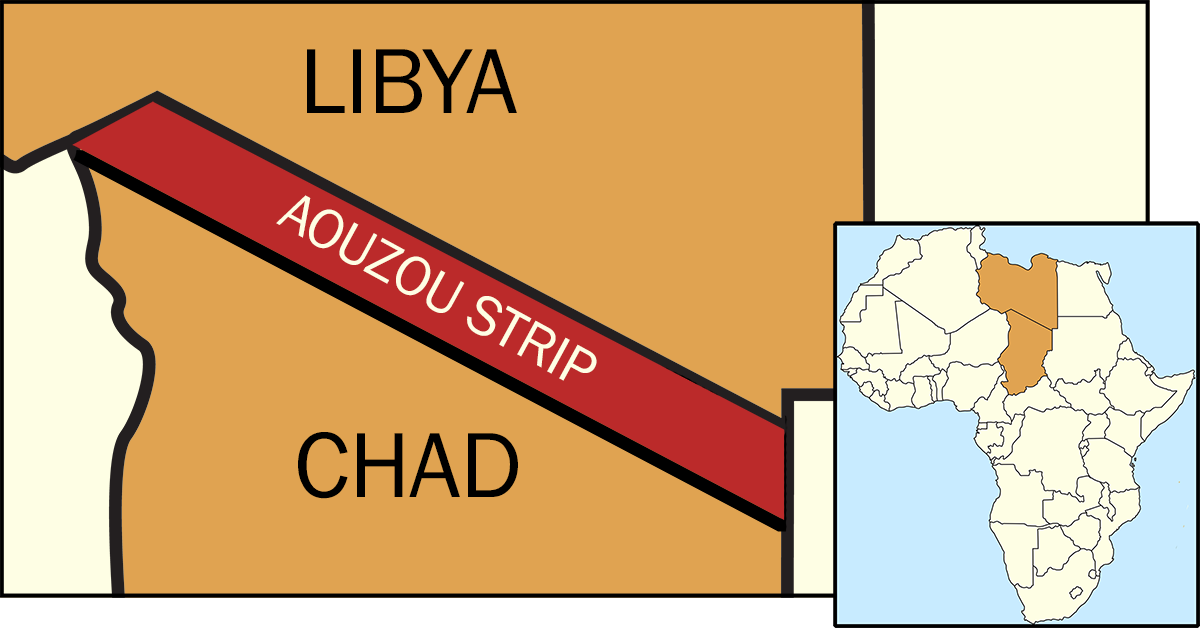

A point of contention was their shared north-south border, a 38,000 square mile / 100,000 square kilometer desolate region with little intrinsic value called the Aouzou Strip. The territory is part of the Sahara Desert, a landscape of fine sand that inhibits travel. Few roads traverse the region. Behind Chad’s northern border, this inhospitable, worthless land was coveted by Libya.

Libya: An Overpowering Aggressor

The land defined by Libya’s borders was historically tribal, with ties to ancient civilizations. Strategically located, Libya’s northern coastal border with the Mediterranean Sea supported Arabian trade caravans for centuries. Otherwise – except for petroleum deposits, discovered in the 1950s – the country is resource-poor. Less than 5 percent of Libya’s territory is economically useful.

Libyan society remained nomadic until the state was modernized under Italian colonialism. The Kingdom of Italy invaded Tripoli in October 1911 in pursuit of economic interests. By 1931, after conquering the territory, Italy commenced to make Libya an Italian province – their “fourth shore.” The borders of the present state of Libya were drawn in 1934, and Libya was incorporated into Italy in 1939.

A 1935 secret agreement with France (Chad’s colonial ruler) to relocate the shared border for Libya’s benefit, about sixty miles south, would have far-reaching consequences. Never ratified by the French legislature, this agreement would be used by Libya in the 1980s to justify their attempted annexation of the region, leading to the Toyota War.

Italy extensively modernized Libya, with the goal of exploiting cheap labor and encouraging Italian migration to relieve unemployment and overcrowding in the homeland. The benefits of modernization did not extend to the nomadic Bedouin tribes, whose grazing lands were claimed by colonists. Natives were excluded from Italian education and opportunity. The consequences of this exclusion would be evident in future revolutions.

Libya gained independence following World War II after supporting the allies in the North African desert war. An independent constitution was ratified in October 1951, making Libya a pro-western federal monarchy. Libya, dependent on foreign aid from the US and other nations, was technically an independent nation. But independence did not unify the country.

A titanic change of fortune befell Libya in 1959 when major deposits of high-quality petroleum were discovered in its territory. The petroleum windfall brought riches to Libya. This tremendous wealth would enable one of the 20th century’s most notorious dictators, Colonel Muammar Gaddafi.

The September 1969 Libyan Revolution overthrew the Libyan monarchy in a bloodless coup. The military coup was broadly popular, fueled by dissatisfaction from oil revenue disparity, corrupt government, and anger directed towards western influence. Gaddafi rose to lead the post-revolution nation as Commander in Chief and Chief of Armed Forces. Charismatic, confrontational, mercurial, idealistic, the populist leader brought cohesion to Libya and a new national identity. As dictator, his name became synonymous with his country.

A staunch proponent of pan-African, Islamic unity, Gaddafi’s outreach was not always appreciated by African or Western nations. Gaddafi espoused a mix of revolutionary socialism and Islamic religious law, formally naming the country “the Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya [state of the masses].” His desire for power across Africa and Arabia put Chad in Libya’s crosshairs.

Gaddafi was emboldened by the outsized Libyan military he funded with Libya’s oil fortune. By 1986, Libya was the fifteenth top producer of petroleum. Its coastal border and modern infrastructure enabled the lucrative export of Libyan oil. Motivated by his megalomaniacal vision of a unified Arabia and seeking to raise his stature amongst the Arab world, Gaddafi in the 1980’s was an infamous sponsor of international terrorism. Gaddafi directed the murders of hundreds of civilians and US service members in Europe and West Asia.

Libya suffered western economic and travel sanctions in retaliation yet found advanced weapons readily available from the Soviet Union and Europe, paid for with abundant oil funds. The Soviet Union, despite Gaddafi’s fierce anti-communist stance, supplied the vast majority of weapons to Libya, followed by Italy, France, and West Germany. A massive arms build-up in the 1970’s and 1980’s, and compulsory military service for men and women, swelled Libya’s over-equipped military. In 1985, Libya’s growing forces included 58,000 active conscripts, 2,800 battle tanks, 1,200 armored cars, 1,160 half-tracks, and 535 aircraft (including bombers, fighters, and reconnaissance aircraft), as well as a navy with over fifty vessels.

Libya possessed far more weapons than needed for self-defense. In fact, the stockpile exceeded their operational capacity. Many of the weapons, vehicles, and equipment remained in storage, never used. Much of the arsenal was not serviceable, the Libyan Army being incapable of maintaining such advanced weaponry. Limitations in training, staffing and maintenance, and widespread dissatisfaction in the military limited the capability of Libyan forces. Libya soundly outgunned Chad, but the ineptitude of Libya’s military operations against Chad in the 1970’s and 1980’s would lead to a definitive Libyan defeat.

Chad: The Improbable Victor

Chad was once the crossroads of lucrative trans-Saharan trade routes. Its central location on the African continent attracted numerous cultures. Modern Chad has more than two hundred ethnic groups and over one hundred languages spoken (Arabic and French being the national languages). Regional and nomadic Chadian warlords, rebels, clans, kingdoms, and sultanates would later chafe under government rule. By the end of the 19th century Chad was one of the most impoverished nations in the world.

Chad is a landlocked African nation with an unevenly distributed population that is separated by regions of inhospitable climate and geography. By 1987, Chad’s development had been encumbered by authoritarianism and a 1965-1979 civil war. Poverty was pervasive, aggravated by drought in the African Sahel in the 1970’s and the government’s inability to provide drought relief. In 1987, at the start of the Toyota War, Chad had no railroads, no paved roads, and poorly developed telecommunications. Citizens of Chad often lacked access to electricity and sanitation. Literacy rates were low, as was life expectancy.

Like Libya, Chad’s modern history is shaped by colonialism. French colonists arrived in the late 1800’s, after the fall of Chad’s former kingdoms, seeking exploitable wealth by means of large-scale cotton plantations and unskilled labor. However, the French military occupation had limited control and less cultural influence over Chad’s sparsely populated, arid north. From 1905 to 1920, Chad was administered as a part of “French Equatorial Africa” with three other colonies. France ruled Chad indirectly through sultanates, governed indifferently, and made minimal effort to modernize the country (especially the resource-poor north, the contentious borderland shared with Libya’s southern border).

Chad gained independence from colonial France on August 11, 1960. Soon after, tribal and ethnic tensions, no longer suppressed by French rule, boiled over to factional fighting. Civil war would follow in 1965, with Chad ruled by dictator François Tombalbaye. Following years of a declining economy, ethnic and regional conflict, corruption, and repressive authoritarianism, the post-colonial government led by Tombalbaye fell in a 1975 coup d’etat and assassination. A series of authoritarian regimes under military rule followed. Whereas the discovery of oil propelled Libya’s modernization, no such luck would save Chad.

Political, ethnic, and religious strife froze Chad’s progress in the 1970’s and 1980’s. A plethora of political, ethnic and religious factional divisions formed in the power vacuum after the coup d’etat that disposed Tombalbaye, some supported for political gain by neighboring Libya: the Supreme Military Council (Conseil Superieur Militaire – CSM), the Northern Second Army (Forces Armees du Nord – FAN), the National Liberation Front of Chad (Front de Libération Nationale du Tchad – FROLINAT), the Command Council of the Armed Forces of the North (Conseil de Commandement des Forces Armées du Nord – CCFAN), the People’s Armed Forces (Forces Armees Populaires – FAP), the Transitional Government of National Unity (Gouvernement d’Union Nationale de Transition – GUNT). Libyan “liberation fronts” took advantage of the chaos, increasing tensions between the two countries. GUNT, financed by Libya to support their geopolitical objectives, would in particular play a decisive role in the ensuing Toyota War.

The US, in its game of geopolitical chess, offered military aid to Chad to counter Gaddafi’s influence. The offer was intended to match Gaddafi’s forces with deliveries of tanks and heavy weaponry. The Chadian army lacked experience with armored vehicles and had no trained maintenance crews to keep them running. Chad was also incapable of supplying large mechanized forces in battle. In a decision made with remarkable foresight, Chadian dictator Hissène Habré’s cabinet declined the US’s initial package. Recognizing the impracticality of conventional military aid, they requested light, maneuverable vehicles like the Toyota Hilux. This decision would prove instrumental in the coming conflict. In Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948-1991, Kenneth Pollack notes, “to their credit, Habré and his subordinates recognized which equipment would be useful to them and which would simply be a hindrance. They declined offers of tanks, APCs [Armored Personnel Carriers], and heavy artillery and instead requested light armored cars, trucks, automatic weapons, grenade launchers, recoilless rifles, mortars, antitank weapons, and antiaircraft weapons.”

The Toyota War: Ingenuity Against Might

The Toyota war is recognized today for the stunning victory of the outmatched Chadian National Armed Forces (Forces Armées Nationales Tchadiennes – FANT) against the heavily-armed, Soviet-trained Libyan military, accomplished with a cavalry of Hilux pickups and tactics tailored for the machines. The Hilux technicals, constantly maneuvering to prevent being targeted, gave Chad the means to fight offensively against Libyan armor.

FANT, led by Chadian Commander-in-Chief Hassan Djamous, adapted centuries-old desert cavalry tactics for fleets of technicals. As described in the Library of Congress’ Chad – A Country Study, “the main fighting units of FANT, a group that had performed superbly against the Libyans during the 1987 offensive, were young but toughened by several years of harsh desert warfare. Their tactics of rapid movement and sudden sweeps upon an unsuspecting enemy were reminiscent of their nomadic warrior forebears.”

The outcome of the Great Toyota War was determined at the Aouzou Strip. There are few exploitable resources in the Aouzou Strip, but exploratory surveys in the 1980’s reported deposits of uranium. Given Gaddafi’s ambition for an arsenal of nuclear weapons, a uranium source was a prized target. The disputed border became the backdrop for an unexpected showdown that would reshape the narrative of the war.

Soon after gaining power, Gaddafi established camps in the Aouzou Strip to train Chadian and other African dissidents, with the goal of exploiting Chad’s instability and extending Libya’s influence. Libya claimed the Aouzou Strip based on ethnic and religious ties, and the unratified 1935 border adjustment agreement between France and Italy. Libya also claimed historical and political connections with Indigenous people in the Aouzou Strip. In fact, many northern Chadians identified more closely with Libya than the ruling ethnic powers in Chad, and interaction across the border by migrating Saharan tribes was common. Libya occupied the Aouzou Strip after striking its secret agreement with Tombalbaye in 1972, and fully annexed the Aouzou Strip in 1975.

In the Aouzou Strip, Libya amassed 8,000 soldiers, three hundred tanks, sixty combat aircraft, artillery, and rocket launchers across several permanent bases. Of these bases, Ouadi Doum Air Base had the greatest strategic value. Ouadi Doum was a direct threat to Chadian sovereignty. The Libyan Army used Ouadi Doum as a jumping-off point for incursions into Chad, as a forward base for resupply flights, and as a supply base for the Chadian rebel factions sponsored by Libya. Ouadi Doum was also a source of terrifying aerial attacks.

The years-long conflict was won in two battles: The Battle of B’ir Kora in March 1987, which decimated Libyan forces in two engagements, and the Battle of Ouadi Doum, also in March 1987, which captured Libya’s main base in the Aouzou Strip. FANT conducted military operations with Hilux and other technicals throughout Chad’s civil war, but the Toyota War is most remembered for the Chadian victory at the Battle of Ouadi Doum.

FANT succeeded by developing new battle tactics that exploited the strengths of technicals against heavy armored tanks. Before engaging in battle, FANT had a clear picture of Ouadi Doum’s defenses by analyzing extensive intelligence supplied by the US and France, including satellite imagery. Years of desert skirmishes in Chad’s long-running civil war honed the battle tactics of Djamous’ FANT attack force. Also aiding FANT: GUNT, the pro-Libya rebel faction financed by Gaddafi, turned against Libya when economic assistance failed to materialize and political maneuvering caused dissension within the coalition. Libya was left to defend their Aouzou Strip outposts alone, without aid from experienced open terrain fighters.

The Battle of B’ir Kora

The Battle of B’ir Kora was the first phase of the mission to capture Ouadi Doum Air Base. To reduce the defensive ranks at Ouadi Doum in anticipation of its capture, FANT conducted harassment campaigns with speeding Hilux trucks in the vicinity of Ouadi Doum to lure Libyan forces into the open desert. These agile vehicles were modified with bed-mounted, French-supplied anti-tank weapons, machine guns, or rocket launchers – lethal combinations.

In early March 1987, two Libyan armored columns left Ouadi Doum, including 1,500 Libyan troops and one hundred armored vehicles and tanks. Perhaps the Libyan Army was lured by FANT’s trap. Or, the force may have been on a mission to recapture the city of Fada, 115 miles northwest, after suffering a humiliating defeat at the hands of FANT in January. Whatever the reason for the operation, few would return. In the course of the columns’ trek, they stopped their advance for an unexplained two-week delay, thirty miles outside Ouadi Doum. It’s there that FANT made their crushing first strike, on March 19, 1987.

A FANT offensive force of 2,500 soldiers in four hundred Toyota Hilux and Land Cruiser vehicles (along with some French and US armored cars) rapidly destroyed Libyan T-55 tanks. The Libyan Army’s slow-moving frontal assault was helpless in the chaos. Plodding Libyan tanks, bogged down in powdery desert sand, were easy targets for the fast, nimble pickups. Toyotas fanned out and attacked the Libyan armored column from all directions, swarming and isolating the tanks. Probing attacks identified weaknesses in the column. The high-caliber guns and French Milan anti-tank guided missile launchers mounted on the trucks made for devastating close-range flank shots. Rapid retreats made targeting them with lagging tank turrets impossible.

The Libyans’ inflexible, Soviet-trained maneuvers left them unable to respond effectively to FANT’s diversionary attacks. Surrounded and divided, the tank battalion was unable to shift forces and defend their column. The attack came as a complete surprise, given the lack of aerial or ground reconnaissance on the part of the Libyans. In their wake, FANT left a graveyard of wreckage and corpses. Twelve miles from Ouadi Doum, the Toyota cavalry ambushed and defeated a second Libyan tank platoon that had been dispatched to rescue the first (again, inexplicably, with no Libyan air cover or reconnaissance). As the New York Times reported at the time, “the Chadians fought the desert battles in their own fashion, using weapons and tactics with which they were comfortable, such as charges in armed pickup trucks. However unorthodox their approach to warfare may appear to others, to them it was a modernized version of tactics they have used in the desert for centuries.”

The surprise attack laid bare the vulnerabilities of the Libyan military, setting the stage for the next battle. Ouadi Doum, Libya’s largest air base in the north and operational headquarters for the Aouzou Strip, was now in FANT’s sights.

The Battle of Ouadi Doum

At Ouadi Doum, a seemingly impregnatable airbase, squadrons of Libyan fighters, bombers, and attack helicopters, 200 – 300 tanks and 3,000 – 5,000 soldiers, along with armored personnel vehicles, artillery, missiles, and radar, awaited the arrival of FANT. However, these soldiers were undisciplined and unprepared for an attack by fast, mobile Hiluxes. Ouadi Doum operated so dysfunctionally that no scouts patrolled the base, leaving it in the dark about the impending attack. The Libyan Army depended on the superior firepower of their Soviet and European weapons for defense but were unprepared to operate them. Low morale and low unit cohesion also contributed to Libya’s defeat at Ouadi Doum. While Libya’s Aouzou Strip bases were well appointed, few soldiers wished to be stationed in Chad. The territory they defended was not their homeland. News of the slaughter at B’ir Kora further demoralized and terrified Libyan soldiers.

On March 27, 1987, a Hilux cavalry of 2,000 to 3,000 FANT soldiers attacked the base from two points simultaneously. After traversing defensive minefields that surrounded the perimeter, the abandoned base was easily captured within four hours. (Some attacking Chadians incorrectly believed that the Hilux technicals were light and swift enough to safely pass over mines without triggering them. Libyans also suffered high casualties running through their own mine fields attempting to flee.) The soldiers stationed at Ouadi Doum put up no counteroffensive, crumbling in the face of the fast and mobile Hilux cavalry. They abandoned their posts and fled the base.

The fortified air base was left largely intact, with undamaged aircraft, nearly two hundred tanks and armored personnel carriers, weapons, and supplies left by the fleeing Libyan army. The windfall didn’t directly aid the Chadian cause. Like the Libyans, FANT lacked the expertise to operate the sophisticated weapons, vehicles, and equipment at the captured base. Libya’s attempt to bomb their own abandoned equipment, preventing it from falling into the hands of the enemy, also failed. Libyan pilots were unable to drop munitions with precision at the heights they were forced to fly to avoid FANT anti-aircraft fire. Of a punishing 1,269 Libyan casualties and 438 prisoners of war, only 29 Chadians were killed. The remaining Libyan survivors fled into the desert. Fully one-tenth of the Libyan army was wiped out, with an estimated $1 billion in military equipment captured or destroyed by FANT. As news of the capture of Ouadi Doum reached the Libyan Army, soldiers and officers abandoned other Aouzou Strip outposts in a panic.

The battle of Maaten al-Sarra on September 5, 1987, Chad’s response to Libya’s August capture of the town of Aouzou, seized the Maaten al-Sarra Air Base and disabled Libya’s ability to conduct air strikes. A September 11, 1987 ceasefire negotiated by France followed. The Libyan military was ultimately expelled from Chad. In 1994, the International Court of Justice (a part of the United Nations) found Chad to have sovereign rights over the Aouzou Strip and oversaw the withdrawal of the Libyan military from the region.

The Toyota War’s Legacy

The Toyota war is a well-documented case of a light truck cavalry (including the Hilux) used tactically against a military armed with sophisticated Cold War weapons designed to fight World War III. Chad’s audacious offensive in the Aouzou Strip showcased the effectiveness of asymmetrical warfare, utilizing Toyota Hilux technicals as agile weapons against a conventionally superior force.

The victory had profound repercussions. It not only expelled Libya from Chad but drew Gaddafi’s ire, leading to a series of terrorist attacks that reverberated globally. The US’s $32 million arms contract and sharing of intelligence with Chad is a factor that led to his endorsement of terrorist attacks against western interests, including two passenger airliner bombings: US Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland on December 21, 1988, and French UTA Flight 7722 over Niger on September 19, 1989.

The use of Toyota technicals, reminiscent of desert horseback cavalry, left an indelible mark on military strategy as a case of innovation triumphing over might.